Spinal Cord GBM Survival Analysis

7/27/2017

Publication is available at Ovid or here.

In my research group at BIDMC, there was a half-finished literature review of spinal cord Glioblastoma multiforme (scGBM). To finish the review I added recent scGBM patient records and carried out a survival analysis, which was all new to me. The idea was to look at all major treatments and fixed patient characteristics across the total population and find those that correlated with improved outcomes.

The value of a review like this was two-fold. First, notable correlations that are robust, like the necessity of radiation (if it correlates with treatment outcomes), is useful information. Second, reviews like it are a useful repository for future investigations of the disease. Given the rarity of scGBM, it’s unlikely there will ever be a clinical trial.

Ideally, all clinicians would, upon diagnosising a patient with a rare disease, submit their patients’ characteristics and treatment information to an anonymized database so it can be stored for future analysis. The SEERs database is one such example but, as will be discussed, lots of useful information is excluded.

Methods

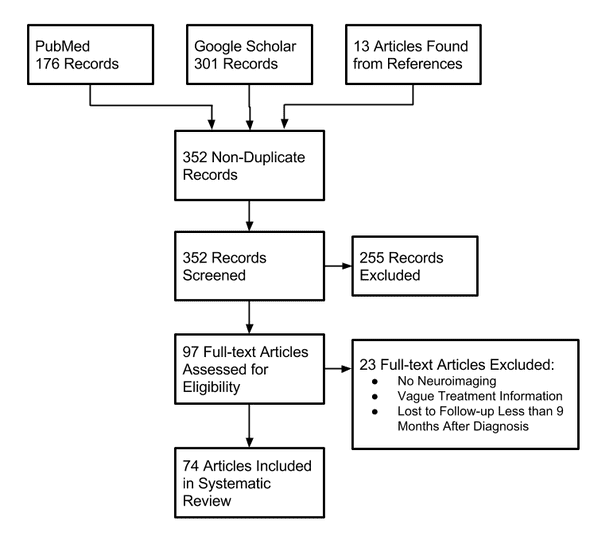

Additional records were found through two sources: PubMed and Google Scholar. First, titles were screened for those that included some combination of “spinal” and “glioma” or “gliosarcoma” or “glioblastoma” in the title. Additional records were identified through the citations, and these were added as well (in a method called “hand-searching”).

Challenges

The primary goal of this analysis was to find treatments that correlate with improved patient outcome. Ideally, this would’ve been attainable with a Cox proportional hazards model with treatments as covariates.

The issue was that codifying treatment of patients, against survival or progression free survival, implies that the treatments are fixed through time. This leads to a common pitfall: immortal time bias. It’s the unintentional assignment of “additional life” to patients that must have lived long enough to have received the treatment.

Immortal time bias can be corrected for when the time of treatment is known for all treatments. So patients are, before having a treatment administered, codified as lacking that treatment. After its administration, they’re converted to the treatment group (as far as the CPH model is concerned). The problem with this data-set is that time of treatment information is virtually absent. All but a handful of records, out of ~170 in the literature, lacked time of treatment information. So investigations of how treatments correlated with outcome are out of the picture.

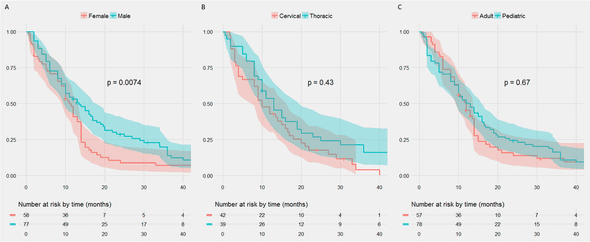

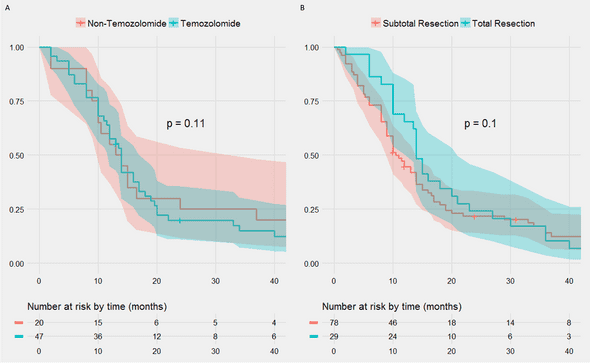

But other questions remain — like how age at diagnosis, sex, and tumor location correlate with outcome (none of which are variable with time). We also compared survivals within treatment groups when only the degree or type of treatment differed. For example, we compared subtotal vs total resection, since both are, likely, administed at the same time in a patient’s treatment timeline.

Results

No treatment type correlated with significant differences in overall survival.

The female sex was very negatively correlated with overall survival, but nothing else reached significance (log-rank p-value on the Kaplan-Myers).

Conclusions

While learning about the cox proportional hazards model and survival analysis was enjoyable, the dataset was unfortunately lacking. It’s suprising that more information isn’t reguarly collected, and it’s hard to image an improvement in understanding of the disease so long as there’s partial data collection.

One solution would be to require, on submission of a case report to a medical journal, a checklist of information. The checklist would include detailed information, such as time between diagnosis and each treatment administed, so time-dependent CPH models could be generated. It’s suprising this is not already a standard requirement, but, even in the case reports post-2015, there was consistently inadequate information. Second, a centralized database could be put in place. This seems less likely for concerns of patient privacy.